The Unhelpful Thinking Patterns I See Most Often in Therapy

Let me paint a picture for you. It’s a Sunday afternoon. I usually do most of the driving because my partner drives a lot for work. I happily take this on as an act of service in our relationship. On this particular day, I’m driving us to the movies. This was back when I-285 was going through major construction, and I missed our exit… not once, but twice.

In that moment, a voice in my head said, “Well, if he just drove us every once in a while, this wouldn’t have happened.” I literally put on the metaphorical brakes. Where did that come from? This is a perfect example of a cognitive distortion called personalization. I was blaming him for something that was entirely my fault, simply because I wanted to deflect some of the embarrassment and discomfort I felt.

These moments happen to all of us. Our brains are wired to make quick sense of situations, often by shifting blame, amplifying negatives, or filling in the blanks with stories. Recognizing these distortions is the first step in noticing them in your own thoughts and learning to respond differently.

In my last post, we talked about how relationships can get stuck when we assume negative intent instead of giving the benefit of the doubt. That same dynamic shows up not just between partners, but inside our own minds. Many of the struggles clients bring into therapy are not caused solely by what happened, but by the meaning their brain automatically assigns to it.

These patterns are not signs that something is “wrong” with you. They are very human shortcuts our brains use to make sense of the world, especially when we are stressed, hurt, anxious, or overwhelmed. The problem is that these shortcuts often backfire, increasing distress and narrowing our options for responding.

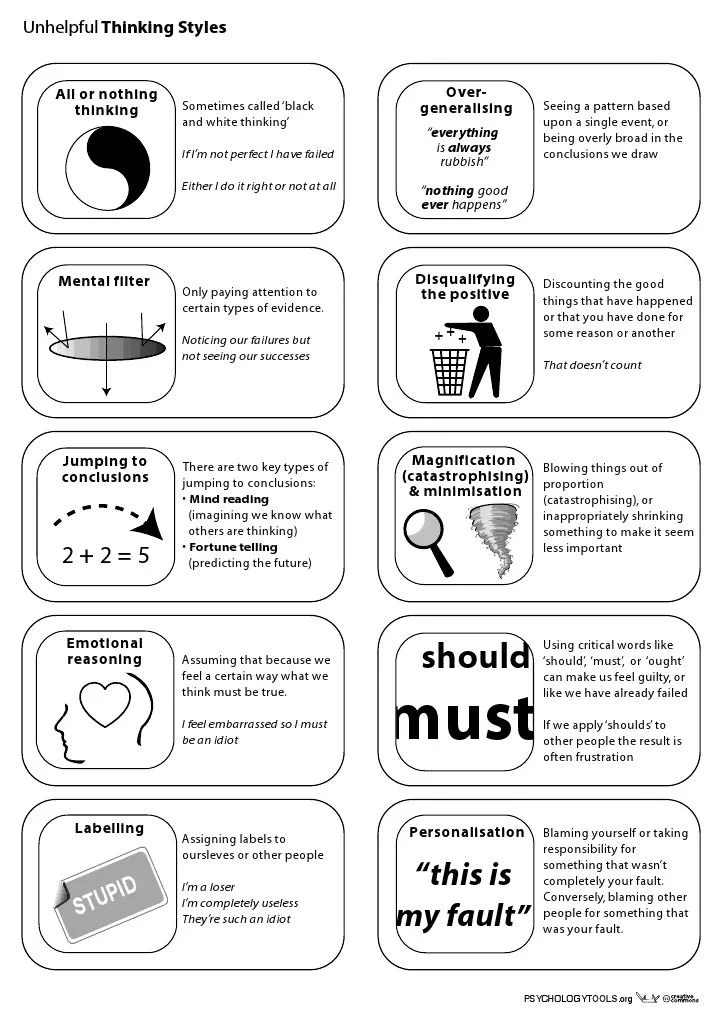

Below are some of the most common unhelpful thinking patterns I see in my work with clients.

Quick cheat sheet on cognitive distortions, or unhelpful thinking styles.

Black-and-White Thinking, or All or Nothing Thinking

This is the tendency to see things in extremes, with no middle ground. Something is all good or all bad, a success or a failure, loving or rejecting.

Examples:

“If I’m not doing it perfectly, I’m failing.”

“If they really loved me, they would never forget this.”

Real life usually lives in the gray. When we force situations into extremes, we miss nuance, growth, and repair.

Overgeneralization

This happens when we take one experience and apply it broadly, often using words like always, never, or every time.

Examples:

“This always happens to me.”

“I never get it right.”

One moment becomes a sweeping conclusion about who you are or how the world works.

Mental Filter

With a mental filter, the brain zooms in on one negative detail and ignores everything else.

Example:

You receive ten positive comments and one critical one, and the critical comment is all you can think about.

This filter can make life feel far more negative than it actually is.

Disqualifying the Positive

This pattern goes a step further than a mental filter. Even when something positive happens, the brain finds a way to dismiss it.

Examples:

“They’re just being nice.”

“That doesn’t really count.”

Over time, this erodes self-worth and makes it very hard to take in support or affirmation.

Jumping to Conclusions

This includes mind reading and predicting the future without enough evidence.

Examples:

Mind reading: “They didn’t text back, so they must be mad at me.”

Fortune telling: “This conversation is going to go terribly.”

Our brains are excellent storytellers, but not always accurate ones.

Magnification (Catastrophizing)

Here, the brain blows things out of proportion and jumps straight to worst-case scenarios.

Examples:

“This mistake is going to ruin everything.”

“If this doesn’t work out, I’ll never recover.”

Catastrophizing creates intense anxiety and urgency, even when the actual risk is manageable.

Minimization

Minimization downplays needs, feelings, or experiences, often to keep the peace or avoid conflict. This can show up as dismissiveness toward oneself or as fawning behaviors.

Examples:

“It’s not that big of a deal.”

“Other people have it worse, so I shouldn’t complain.”

While it may feel selfless, chronic minimization often leads to resentment and burnout.

Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning treats feelings as facts.

Examples:

“I feel like a burden, so I must be one.”

“This feels unsafe, so it must be unsafe.”

Feelings are real and important, but they are not always reliable evidence.

‘Shoulding’ and ‘Musterbation’

This pattern is built around rigid rules for yourself or others.

Examples:

“I should be over this by now.”

“They must always handle things the right way.”

These internal rules often create shame, pressure, and chronic dissatisfaction.

Labeling

Labeling reduces a whole person, often yourself, to a single word based on behavior or mistakes.

Examples:

“I’m a failure.”

“They’re selfish.”

Labels feel definitive, but they erase context, complexity, and the possibility of change.

Personalization

Personalization involves taking responsibility for things that are not actually about you.

Examples:

“They’re quiet today, I must have done something wrong.”

“This is my fault.”

This pattern can create unnecessary guilt and anxiety, especially in relationships.

A Gentle Reminder

These thinking patterns are not flaws. They are habits, and habits can be noticed, challenged, and softened. Awareness is the first step. When you start to recognize these patterns in your own thoughts, you create space to ask different questions, consider alternative explanations, and respond with more flexibility and compassion.

In upcoming posts, I’ll break these down further and talk about practical ways to work with them, not by arguing with your brain, but by understanding it.

If you recognized yourself in several of these, you’re not alone. This is the work, and we’re all guilty of these!

Sources and Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more about these thinking patterns, the following books and resources are foundational and widely used in therapy:

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press.

Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. HarperCollins.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Greenberger, D., & Padesky, C. A. (2016). Mind Over Mood (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Ellis, A., & Harper, R. A. (1997). A Guide to Rational Living. Wilshire Book Company.

These concepts are core components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and related evidence-based approaches used to help clients notice, challenge, and soften unhelpful thought patterns.